A Debt Ceiling Deal Is Near-Term Risk For Stocks

Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

Far from being a risk-on stimulus, a debt-ceiling resolution will expose stocks to a correction as the resulting increase in Treasury issuance sucks liquidity from the system.

With all the banal inevitability of rain on your day off, debt-ceiling negotiations are threatening to go to the wire. For now, expectations are still for some sort of agreement to be reached, with equity investors adding this to their quiver of reasons to be bullish.

No agreement would be negative for stocks, but even a detente is likely to lead to risk-off moves in markets. A debt-ceiling extension would allow the Treasury to ramp issuance back up, leading to a drop in central-bank reserves and bank deposits, absorbing liquidity and sparking a notable short-term correction in equity markets.

Net issuance in both T-bills and bonds has dwindled to almost zero as the debt limit approaches. The Treasury has been drawing down its account at the Federal Reserve (the TGA) to fund spending it would normally pay for through borrowing. Overall liquidity has thus remained supported while the politicians sow confusion and disruption.

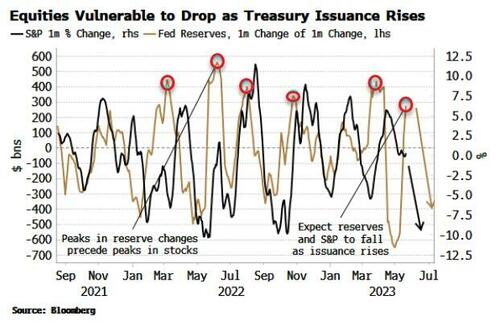

But new issuance is like a liquidity hoover, sucking up Fed reserves and, as the chart below shows, leaving stocks prone to downside.

The key question is, will reserves fall as the Treasury issues more debt? The risks are firmly tilted in this direction. To see why, we need to consider who is likely to buy new Treasury debt and how this affects bank deposits and reserves.

The most detrimental effect is if households or corporates purchase the debt. That’s because bank deposits are used to make the purchase. Now, if the Treasury spent all of the proceeds, they would end up as deposits elsewhere, i.e. deposits overall would be unchanged.

However, the Treasury projects it will refill the TGA to $550 billion by the end of June (currently at $57 billion), which means that many deposits, and reserves, will disappear.

On the other hand, if a bank buys the Treasury debt, reserves will likely fall, but bank deposits should remain unchanged. That’s because no deposit-holder is involved in the purchase, while most of the reserves are likely to be absorbed by the TGA as the Treasury refills it.

When a money-market fund buys a T-bill, it depends on whether it’s investing new money or not. If the money comes from a bank (escaping still significantly lower deposit rates versus MMF yields), then deposits and reserves will fall if the Treasury refills the TGA with the proceeds. But if the MMF takes reserves from the RRP facility, then deposits and reserves will remain unchanged.

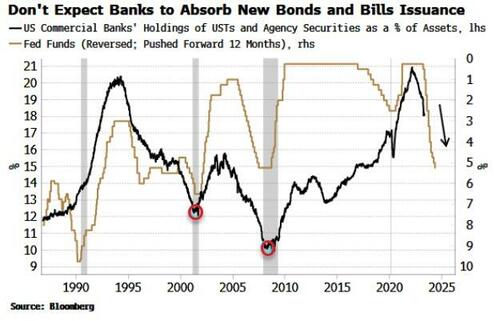

Unfortunately, banks or MMFs will be unlikely to shoulder much of the new-issuance burden.

Lenders are already too long of duration (as recent bank failures have highlighted). And as the chart below shows, banks typically reduce their duration risk in response to higher rates. Even after some recent divestment, there is likely a lot more to come.

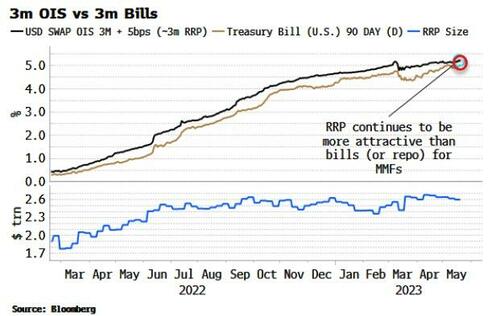

MMFs are unlikely to be much help either. For a start, they only buy T-bills, not longer-dated notes and bonds. Secondly, the rate offered on the RRP facility continues to be more attractive than 3-month bills. MMFs are therefore unlikely to want to switch into them from the RRP.

That may change in due course, however, if bill issuance pushes yields higher than the RRP facility. Furthermore, a peak in rates will eventually mean the 3-month rate will drop below the overnight rate, making the RRP less attractive. But for the time being, MMFs are likely to maintain their preference for the RRP.

Will foreigners come to the rescue? Total overseas UST holdings remain below last year’s peak. EM global reserve managers are trying to diversify their holdings so they are less concentrated in dollars, while large DM holders of Treasuries, such as energy importers like Japan and Switzerland, have been selling reserves in the order of hundreds of billions of dollars.

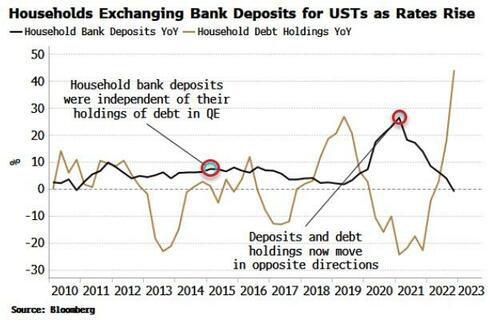

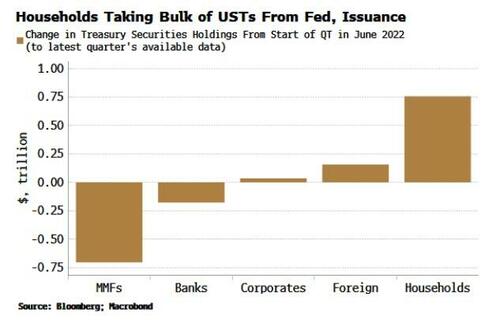

We are thus left with households and corporates who will most likely absorb the majority of the new issuance. As the chart below shows, this means bank deposits are likely to continue falling, and with them, reserves.

Households have already been doing the heavy lifting, the sector adding $750 billion to their UST holdings over the last half of 2022 (the latest period we have data for), much more than any other sector.

That trend is poised to continue as the Treasury increases issuance (projected to be over $2 trillion for FY2023) and the Fed proceeds with QT, thus wicking away liquidity.

Equities – even if the medium and longer-term picture is improving and underweight investors are chasing the market – are therefore not home and dry yet, and are liable to face some – potentially sharp – short-term downside once the political theatrics are over.

Tyler Durden

Tue, 05/23/2023 – 08:20